Chapter 7

The University, the Gate,

and ‘the Gadget’

Named Berkeley for the author of the portentous line “Westward the course of empire takes its way,” the University of California occupied a site fortuitously facing the Golden Gate. A master plan funded by the Hearst fortune organized the University around a central axis aimed at the Gate “for Alma Mater’s peaceful and beneficent conquest of far Oriental realms” according to its designer. The arrival of physicists Ernest Lawrence and Robert Oppenheimer in Berkeley within a year of each other just before the Crash of ’29 set the stage for discoveries in atomic fission that would lead to the development of nuclear energy and weapons, the super-energy of the future feared by historian Henry Adams as early as 1905. It would also engage the University in the development and production of ever-more advanced generations of nuclear weaponry while giving sudden value to uranium mining and related industries in which University Regents were heavily involved.

This ubiquitous image shaped the outlook of the postwar genera tion. Illustration by Chesley Bonestell for Look, April 21, 1953.

Notes

1. Ironically, the 1906 quake felled the arch within seconds.

2. “From California and from the Pacific coast must radiate the life to graft the principles of liberty upon the ruins of the dying empires of the Orient. Upon western men and upon western women has fallen the privilege of advancing the fulfillment of their Nation’s destiny.” Merrack, “Stanford University,” 104.

3. For the story of the competition and its local and national repercussions, see Brechin, “San Francisco: The City Beautiful.”

4. Partridge, John Galen Howard andthe Berkeley Campus, 12.

5. Edward F. Cahill, “Benjamin Ide Wheeler Is the True Gibson Man,” San Francisco Examiner, 23 August 1899.

6. Payne, “City of Education, Part II. “The Greek analogy was already a commonplace by 1900 when the Overland Monthly noted, “The prophecy has often been made that [California] was destined to become a second Greece. The art, the love of beauty, the passion for culture, are all here in the germ. May the quickening touch of the new President of the State University do its work in causing them to grow!” “Two University Presidents,” 183-84.

7. The unfortunate culmination of the great competition is related in a letter from Regent Jacob Reinstein to Professor T. Leuschner, 1December I 899, Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers.

8. Hearst could ill-afford the money for the theater at the time, but needed a device to cleanse his soiled reputation. Enemies charged that his incendiary papers had incited an anarchist to assassinate President McKinley at the Buffalo world’s fair in 190 1, and Hearst’s satyric private life did little to aid a man with presidential ambitions. At the dedication of the theater, Hearst owned seven newspapers and Motor Magazine.

9. Ackerman, “President Roosevelt in California,” 108.

10. See Reiss and Mitchell, Dance at the Temple of the Wings.

11. While assembling the Homestake Mining Company, Hearst wrote his partner J. B. Haggin in 1878, “I will hurt a good many people. And it is quite possible that I may get killed. All I ask of you is to see that my wife and child gets [sic] all that is due them from all sources and that I am not buried in this place [i.e., Lead, South Dakota].” Cieply, “Loded Hearst,” 76-77.

12. The builders were unaware that the building was sited almost on top of the Hayward Fault.

13. Jack London, “Simple Impressive Rite,” San Francisco Examiner, 19 November 1902.

14. Howard, “Architectural Plan,” 282-83 .

15. Wheeler tied the university’s destiny to those of the arms makers from the moment he arrived: “A harbor that produced [Dewey’s] Oregon deserves to have by its side a school of naval and marine engineering.” Wheeler, “University of California and Its Future,” 7. Encomia to the Union Iron Works’ battleships were common in the years after Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay.

16. The theme remained one of Wheeler’s most consistent. See “Pacific States and the Education of the Orient,” 1-5, in which the university’s president voices the fear that if China became armed with “modern steel weapons; i.e., machinery, engines, dynamos, and rails, it means, of course, an economic revolution and an upturning from the depths. “The United States must prepare itself to resist the onslaught as the Greeks resisted Persia,” claimed Wheeler. As noted earlier, see Glacken, Traces on the Rhodian Shore, 276-82, for intellectual history behind such “prophecies. “

17. “Inauguration of President Wheeler,” 26 1, 26 5-67.

18. “Commercial Museum,” 67-70. See also Wilson, “San Francisco’s Foreign Trade,” 6; “The Two Commercial Museums of the United States,” San Francisco Chronicle, r8 October 1903; and Wright, “Development of the Philippines,” 8083-90.

19. The Philadelphia Commercial Museum was founded by Dr. William Pepper-Phoebe Hearst’s personal physician and close friend as well as provost of the University of Pennsylvania-with raw materials obtained from the Chicago world’s fair. See Plehn, “ Memorandum,” 3 66-68.

20. Stadtman, Centennial Record of the University of California, 99.

21. Dorfman, Economic Mind, 96-98.

22. Moses, “University and the Orient,” 24.

23. Moses argued that races should be segregated in the United States for their own good, but that in the Philippines, “it would be bringing together, not two races, but two kindred peoples, of whose amalgamation nature seems to approve.” “Bernard Moses on the Philippines,” 4-5. See especially the section “Right Kind of Exploiting Needed. “

24. Moses, “University and the Orient,” 2 3-24.

25. Moses, “Control,” 96.

26. Ibid., 84.

27. See Moses, “Great Administrator,” 4222-29, with photographs of the triumphal arches built for Governor Taft’s processions through the islands.

28. “Education Must Solve Great Problems in the Philippines,” San Francisco Bulletin, 28 August 1903. Extreme as such views might seem, they were consistent with Wheeler’s, and the elite’s, designs for the university. See Reid, “Our New Interests,” 97-98, and Wheeler’s introductory remarks. Reid was publisher of the New York Tribune and son-in-law of former regent Darius Ogden Mills.

29. See Wheeler’s “Biennial Report to the Governor for 1902,” supplement, 53 -60.

30. Cutter, “College of Commerce of California,” 491.

31. Greene, “University of California,” 463.

32. The “awakening” of the Orient required that the university take action: “It is ours to mold their speculative and religious thought. To do this, we ought to know their habits of thought and life, their social conditions and problems.” See “California and the Orient”; and John Fryer, “The Demands of the Orient,” Blue and Gold ( 1900): 25-26.

33. Cheney, “How the University Helps,” 292-93.

34. “The University in the Past Year,” Blue and Gold (1903): n.p.

35. “New Department of Anthropology,” 281-82. Hearst biographer Ferdinand Lundberg says that geologists and metallurgists went along to scout the prospects at the Cerro de Pasco mines, which subsequently were added to the Hearst portfolio.Lundberg, Imperial Hearst, 91.

36. Emerson, “California’s Etruscan Museum,” 458.

37. Greene, “University of California,” 460-61.

38. Reinstein, “Regent Reinstein’s Address,” 342.

39. Moses, “Recent War with Spain,” 411.

40. Moses, “Ethical Importance,” 209.

41. Starr, Americans andthe California Dream, 337-38.

42. F. Walker, “Frank Norris at the University of California,” 331. For an opposing view of football as training for war, see “The Mob of Little Haters,” in Sinclair, Goose-Step, 141 -45.

43. Wheeler, Abundant Life, 328. This book is the authoritative compila

tion of Wheeler’s incidental speeches and platitudes.

44. In his unpublished autobiography, Barrows notes that he taught a seminar in Military Government of Conquered or Acquired Territory under the United States, which was “probably the first such course offered in an American university.” David Prescott Barrows papers, carton 5, autobiographical material.

45. “The Professor Asks Why,” Star, 23 May 1914, p. 3.

46. L. Allen, “Westward,” 47.Eugenics professor S.J. Holmes expressed his own alarm to Dean Barrows that minor medical defects eliminated large numbers of men who otherwise could fight and “materially advance our economic productivity.” S.J. Holmes to Barrows, 11 April 191 7, David Prescott Barrows papers, box 19.

47. Ross, “Suppression of Important News,” 55. Among the callow youths influenced by Jordan’s strident Saxonism was Herbert Hoover, as well as Jack London, who incorporated it in his immensely popular novels.See Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 309.

48. The ensuing furor over the Ross case contributed to the national movement for academic tenure.

49. A Veblen biographer speculates that Wheeler blocked the economist’s appointment to a position at the Library of Congress. See Dorfman, Thorstein Veblen and His America, 257.

50. Wheeler, “Benjamin Ide Wheeler’s Speech,” 190.

51. Lewis, “University and the Working Class,” 255-60.

52. Beck, Men Who Control Our Universities, 1 947, largely confirms Sinclair’s charges.

53. Sinclair, Goose-Step, 127-29, 136. In 1970, the California legislature discovered that top U.C. officials had set up a tax-exempt dummy corporation that profited the regent Edwin Pauley’s oil company far more than it did the university. We will meet Pauley later in the chapter. See Assembly Committee on Education, “Interim Hearing.”

54. “Aims of Better America Body Told Business Men of San Francisco,” San Francisco Call, 20 January 1922. Haldeman was grandfather of President Richard Nixon’s White House chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, who would serve on the board of regents in 1966-67.

55. Ibid.

56. “Astounding Power of an Ounce of Radium,” San Francisco Bulletin, 8 March 1903.

57. Wells, Tono-Bungay, 336.

58. Gilbert Lewis received part of his education in Germany; he served in the Bureau of Science in the Philippines in 1904 and 1905, where he must have known Barrows.

59. May, “Three Faces of Berkeley,” 26-28. For the establishment of a U.C. campus at San Diego as a requested support facility for the weapons contractor General Dynamics, see Treleven, “Interview with Cyril C. Nigg,” 150-52.

60. Van der Zee, Greatest Men’s Party on Earth, II 5; and Childs, American Genius, 497.

61. See Heilbron and Seidel, Lawrence and His Laboratory, on anti-Semitism at the Berkeley Radiation Lab.

62. Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, 444-45.

63. Barrows, “Professional Inertia and Preparedness,” 1 86.

64. University of California, “Addresses Delivered at Memorial Service for Bernard Moses, April 13, 1930,” Berkeley: University of California Printer, 1 93 I.

65. Childs, American Genius, 140.

66. The quote is from “Wirephoto War, “ 49.

67. In 1946, the year that Neylan first took Lawrence to meet William Randolph Hearst at San Simeon, he called the scientist “probably the most significant living human being.” Neylan nominated Lawrence to the even more exclusive Pacific Union Club in 1957, the year before the physicist’s sudden death. Oppenheimer was apparently not invited to join either club.

68. Lawrence to Robert Gordon Sproul, 10 October 1939, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, carton 26, folder 1 . For the importance of alchemical metaphors in nuclear research, see Easlea, Fathering the Unthinkable.

69. Milton Silverman, “Science: Our Town Is a Great Laboratory,” San Francisco Chronicle, 28 January 1940.

70. Lawrence to Alfred Loomis, 13 January 1940, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, carton 46, folder 8.

71. Donald Cooksey to Alfred Loomis, 14 May 1940, Ernest 0. Lawrence

Papers, carton 46, folder 8.

72. Room 307 is now a National Historic Landmark.

73. Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, 372-79.

74. Ibid., 40 1-5.

75. Dr. Eger Murphree, research director of Standard Oil, also attended.

76. Compton, Atomic Quest, 1 53 .

77. Rhodes, Making of the Atomic Bomb, 448.

78. N. P. Davis, Lawrence and Oppenheimer, 186.

79. Oppenheimer called the bomb work at Los Alamos “an organic necessity,” and went on to explain, “If you are a scientist you cannot stop such a thing. If you are a scientist you believe that it is good to find out how the world works; what the realities are; that it is good to turn over to mankind at large [sic] the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and values. “ Easlea, Fathering the Unthinkable, 9 0, 1 29.

80. Richard Rhodes speculates that President Roosevelt “was concerned less with a German challenge than with the long-term consequences of acquiring so decisive a new class of destructive instruments” when he ordered fullscale development of the weapon prior to Pearl Harbor. Rhodes, Making ofthe Atomic Bomb, 3 79. See also Franklin, War Stars.

81. E.g., in 1955, the regent Edwin Pauley secretly used Lawrence as a gobetween to hire Major General K.D. Nichols, general manager of the Atomic Energy Commission, as a “consultant” for thirty-five thousand dollars per year, with a ro percent commission for any business he brought Pauley. Edwin Pauley to K.D. Nichols, 24 January 19 55, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, reel 70, frames 1 57779 and 1 57780.

82. “Notes for First Meeting of Committee on Planning for Army and Navy Research,” 22 June 1944, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, carton 20, folder 8.

83. As chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission’s Advisory Committee on Raw Materials from 1 947 to 19 52, the geological engineer and U.C. professor Donald H. McLaughlin-along with friends closely involved in mining and power-acted to set a base price for uranium supplies bought by the AEC. McLaughlin was, at that time, president of Homestake Mining as well as Cerro de Pasco and a close confidante of the Hearst family. Governor Earl WarrenMcLaughlin’s campmate at the Bohemian Grove-nominated him to the board of regents in 1951, after the university began its nominal management of the weapons laboratories that, in turn, created much of the demand for uranium supplies. After leaving the advisory committee, he took Homestake “aggressively” into uranium production to offset falling gold prices, and acknowledged that “we did very well in uranium.” McLaughlin, “Careers in Mining Geology.” I am indebted to Professor Charles L. Schwartz for allowing me to review his files regarding the conflicts of interest of other U.C. regents. See also Taylor and Yokell, Yellowcake.

84. Lowen, Creating the Cold War University.

85. The first quote in the sentence is from Gray, Great Uranium Cartel, 41.

86. Lawrence served as a consultant to General Electric, American Cyanamid, and Eastman Kodak and was a board member of Monsanto Chemical and the RAND Corporation. His stockholdings in these and related corporations are unknown.

87. Lilienthal, Journals of David E. Lilienthal, 23 9.

88. Stanford is usually credited with spawning Silicon Valley by those who miss the vital connections of the “rival” universities via the demands of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. See Lowen, Creating the Cold War University.

89. David Lilienthal wrote in 1949 , “Reports from LA and Berkeley [Lawrence and Alvarez] are rather awful.” He had heard that there “is a group of scientists who can only be described as drooling with the prospect [of a positive H-bomb decision] and bloodthirsty.” Lilienthal, Journals of David E. Lilienthal, 582. See also p. 577. Pringle and Spigelman, Nuclear Barons.

90. See Broad, Star Warriors, for the ongoing attempts of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the conservative Hertz Foundation to attract the best young men for the development of new generations of weapons. This was one of the repeatedly stated aims of Professor Tuve’s 1 944 memorandum, where Tuve also recommended a “parallel attack [on weapons development] under independent direction.” The AEC commissioner Thomas E. Murray said Lawrence gave him credit for “apply[ing] the principle of competition in the ‘H’ field” by establishing the second weapons lab at Livermore. T.E. Murray, Nuclear Policy for War and Peace, 11 o-r r. For the pacesetter role, see quotes by Herbert York and George Kennan in Udall, Myths of August, 145-46.

91. The regents commissioned author Herbert Childs to write An American Genius: The Life of Ernest Orlando Lawrence for the opening of the Hall of Science.

92. The regent John Francis Neylan wrote to Lawrence in 1947 that attempts to share atomic energy were being “utilized as a political racket domestically and internationally,” and said, “Whether it is because I am 62 years of age, or because I have heard so much about the destructiveness of atomic energy, I have become more or less fatalistic about it and am willing to accept the fact that if the human race wants to commit suicide, I cannot stop it.” As chair of the regents’ liaison committee with the Atomic Energy Commission, however, Neylan was in a favored position to help humanity along. His letter went on to state that public opinion would have to be shaped to stress the positive, rather than negative, aspects of atomic energy. The role of Neylan, William Randolph Hearst’s close friend and proxy, in the cold war arms race has yet to be investigated. The regents Neylan, Donald McLaughlin, and Pauley served on the fund-raising committee for the Lawrence Hall of Science. Neylan to Lawrence, r5 April 1947, John Francis Neylan papers.

93. “Big Study Puts Arms Race Cost at $4 Trillion,” San Francisco Chronicle, 12 July 1995. See also Stephen I. Schwartz, ed., Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998).

94. Wilson, “Nuclear Energy: What Went Wrong?” 15.

95. Eichstaedt, If You Poison Us. The mining geologist and regent Donald McLaughlin admitted that the urani um posed a serious health threat to the Navajo miners, but that nothing could be done about it. Europeans, however, had long ventilated their uranium mines. McLaughlin, “Careers in Mining Geology,” 185.

96. Wolfgang K. H. Panofsky, “The Physical Heritage of the Cold War” (Emilio Segre Distinguished Lectureship; delivered to the Department of Physics at University of California at Berkeley, 28 October 1996), video recording.

97. Udall, Myths of August.

98. More privately, they discussed the need for what they hoped would be a limited nuclear war that would eliminate the Soviet Union. The AEC maintained an office building just off campus on Bancroft Avenue.

99. See the university press release of 4 November r9 56 and letter of Captain J. H. Morse Jr. to Ernest Lawrence, 2 July 19 57, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, carton 34, folder 6, Fallout Press Release file. The “Statement on Radiation Hazards from Fallout or Reactor Wastes from the AAAS,” dated September 19 57, is in folder 14 of the same carton. Lawrence supported continued U.S. testing in a 19 57 report to President Eisenhower claiming that hydrogen bombs could be made 97 percent cleaner. See Lawrence obituary in Time (8 September 1958): 64-65.

100. Childs, American Genius, 406-7.

101. The chairman of the board of regents Edwin W. Pauley told Ernest Lawrence that when he opened his son’s mail, he found a plea from the Friends Committee on Legislation and Dr. Albert Schweitzer to halt nuclear testing for reasons of health. Pauley had the president of the Better America Federation, Major General W. A. Worton, send him a dossier on all those named. Pauley to Lawrence, 9 July 19 57, Ernest 0. Lawrence papers, carton 46, folder 13.

102. For precedents set during World War I, see North, “Civil Liberties and the Law,” 243-62; and Gardner, California Oath Controversy.

103. See Mumford, “Gentlemen, You Are Mad.” The initiation of the nuclear arms race nearly drove Mumford himself mad, and it caused him to lose his earlier optimism in the liberatory possibilities of technology. In The Pentagon of Power, Mumford investigated the link between thermonuclear technology and the atavistic wishes of the earliest sun kings.

A note on the Notes

The notes for this and all other chapters are organised by subsections. Not all subsections have notes. It has not been possible to replicate the context of each note. For context, please refer if possible to the print edition. More information on all the materials cited is available on the further reading page.

John Galen Howard’s plan for the University of California’s campus centered on a strong axis aimed at the Golden Gate. Behind a proposed auditorium modeled on Rome’s Pantheon, the axis continued up a steep hill that would later be crowned with another domed structure. Courtesy College of Environmental Design Documents Collection.

A potent trio of friends: U.C. president Benjamin Ide Wheeler awards U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt an honorary doctorate at the dedication of the Hearst Greek Theater in 1903, while regent Phoebe Hearst looks on. Courtesy University Archives.

Student cadets drill as John Galen Howard’s white City of Learning takes shape behind them. Courtesy University Archives.

Lawyer and regent John Francis Neylan was a close associate of William Randolph Hearst and champion of Ernest 0. Lawrence’s research. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

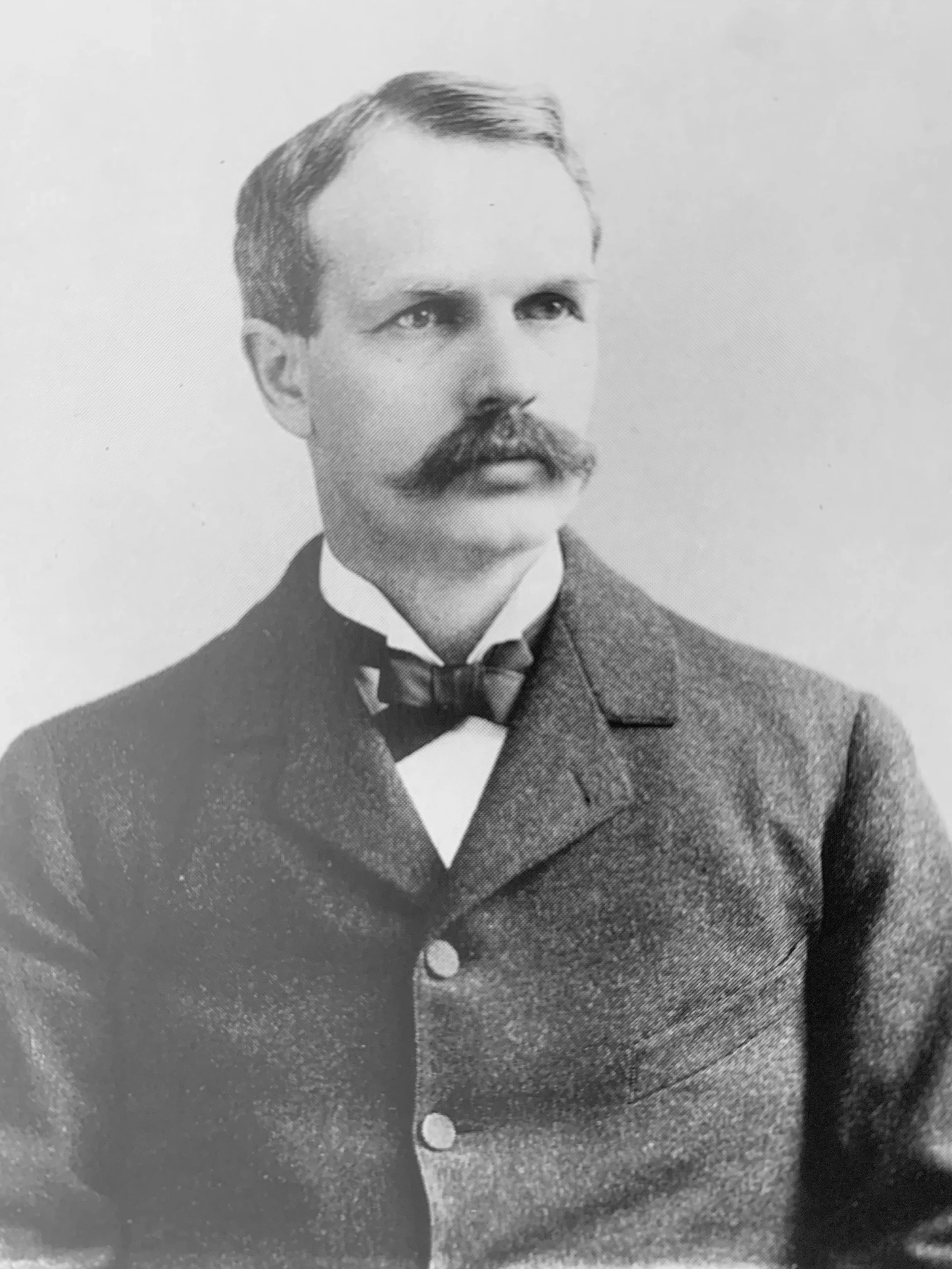

Professor Bernard Moses was founder of the University of California’s Department of Political Science. Courtesy University Archives.