Chapter 5

The Hearsts: Racial Supremacy and the Digestion of “All Mexico”

Born in San Francisco, the flamboyant media mogul William Randolph Hearst built an empire founded on a mining fortune launched by his father in the Comstock Lode. Hearst’s first newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, challenged the primacy of the city’s other leading newspapers, growing to a media conglomerate that spanned the continent and gave the publisher unprecedented power to shape the thought of millions to his own advantage. That power enabled him to foment national belligerence and racial animosity which included his attempt to secure Hearst properties in Mexico by completing the annexation of that country begun by the U.S. in 1848. As a leading exponent of the Yellow Peril, Hearst earned the animosity of Japan.

Casa Grande on Enchanted Hill at the Hearsts’ San Simeon Ranch, of which Julia Morgan was the architect. Credit: Klaus Nahr, Wikimedia Commons.

Notes

1. Takaki, Different Mirror, 173.

2. Brown, Agents of Manifest Destiny, 16.

3. Ibid., 175.

4. Takaki, Different Mirror, 172.

5. Hartford Times, 24 July 1845, as quoted in Merk, Manifest Destiny, 81-82.

6. U. S. Grant, Personal Memoirs, 53.

7. Merk, Manifest Destiny, 140-41.

8. Philadelphia Public Ledger, 25 January 1 848, as quoted in Merk, Manifest Destiny, 124-25.

9. Merk, Manifest Destiny, 235-36n.

10. Fuller, Movement for the Acquisition, 63.

11. Merk, Manifest Destiny, 159.

12. Takaki, Different Mirror, 177-78.

13. Brown, Agents of Manifest Destiny, 423.

14. Hutchinson, “California’s Economic Imperialism,” 67-83.

15. Soule, Annals of San Francisco, 476.

16. A Tennessee aristocrat, Gwin made a fortune defrauding Indians of land and acquiring six hundred thousand acres of newly liberated Texas before coming to California with the specific purpose of being elected senator. See Lately, Between Two Empires, 14-19.

17. Coleman, “Senator Gwin’s Plan for Colonization of Sonora, Part I,” 497-519.

18. Bancroft, Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, vol. 24, 285n.

19. “Our Relations with Mexico,” 64.

20. “South of the Boundary-Line,” 162.

21. “California and Mexico,” 101.

22. At St. Paul’s, Hearst roomed with Will S. Tevis, son of his father’s partner Lloyd Tevis and progenitor of the Bay Cities Water scheme discussed in chapter 2.

23. Hearst, Selections from the Writings, 668-69.

24. William Randolph Hearst to Phoebe Apperson Hearst, undated letter, c. 1890, Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers, William Randolph Hearst correspondence.

25. See “Hearst: A Portrait of the Lower Middle Class,” in Raymond Gram Swing’s Forerunners of American Fascism, 134-52. Built at the same time as the movie palaces of the 1920s, the San Simeon “castle” might be seen as a Paramount Theater built for two.

26. A contemporary and insider remarked that “[George Hearst] was the real founder not only of his own, but of the vast Haggin and Tevis fortunes.” Harpending, Great Diamond Hoax, 117.

27. Hilliard, Hundred Years of Horse Tracks, 71.

28. William Randolph Hearst to Phoebe Apperson Hearst from New York, dated only 1889. Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers, William Randolph Hearst correspondence.

29. See biography of Roy Nelson Bishop in San Francisco Chronicle, 16 January 1915. After Siberia, Bishop was sent to investigate prospects in western Mexico.

30. Hearst wanted the United States to take the Canary Islands from Spain as well, providing the United States with a secure military base in the eastern Atlantic.

31. Makinson, “The Making of a Fortune,” 256.

32. In addition to land registered under the Hearst name, Phoebe owned nearly half of the Real Estate and Development Company, which owned much of Potrero Hill, where property values depended largely on the fortunes of the Union Iron Works.

33. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst, 415.

34. Sinclair, Industrial Republic. Sinclair quickly realized this was one of his most foolish books and never reprinted it.

35. Steffens, “Hearst, the Man of Mystery,” 3–22.

36. Bierce, Collected Works, 305.

37. Ferdinand Lundberg asserts that in 1906, Wall Street insiders used the New York Herald to injure Hearst politically by revealing that the Hearst estate had used the presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan to play the stock market on the side of decline. Imperial Hearst, 86.

38. Sinclair, Brass Check, 94.

39. Porfirio Diaz to William Randolph Hearst, 25 September 1910, Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers, Diaz correspondence.

40. James, Mexico and the Americans, 118-19.

41. See, e.g., Aldrich, “New Country for Americans,” with attendant advertisements for American settlers. Aldrich asked rhetorically, “Can it be possible that all of our boasted enterprise and Yankee shrewdness is but a myth? Are we afraid of an imaginary border line?”

42. Jordan, “Mexico,” 87.

43. During a state visit to Mexico, William Randolph Hearst pledged his support of Mexico and Diaz against the attacks of others, and enthused about the investment possibilities then being opened “for the energetic and the men with capital” in the lands recently cleared of Yaquis. Mexican Herald, 23 March 1910.

44. I am indebted to George Hilliard for sharing his extensive research into the history of the Kern County Land Company.

45. Chamberlin, “United States Interests in Lower California,” 297.

46. Robinson, Hearsts, 207, citing a letter from William Randolph Hearst to Phoebe Apperson Hearst before George Hearst’s election [ 1886?]. In an undated letter of about the same time, he congratulated his mother on the splendor of her equipage in Washington as reported in the newspapers, citing the valuable publicity for the family. See also “Hearst’s Boodle Wins,” New York Times, 19 January 1887.

47. J. M. Hart, Revolutionary Mexico, 283.

48. Groff, “Encyclopedia of Kern County,” 633-34.

49. McArver, “Mining and Diplomacy,” 234-41. Wages at Cerro de Pasco in 1906 ranged from $ 2..50 to $4.00 per day for white men, one-tenth of that for natives. “Cerro de Pasco,” 352-5 5. For the conditions at the mines, see “Absentee American Capital in Peru,” 510-11.

50. McArver, “Mining and Diplomacy,” 98- 101.

51. “Campeche Property of Mrs. P. A. Hearst, “ n.d., Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers.

52. Signed editorial, San Francisco Examiner, 26 December 1898.

53. E.g., “The Examiner’s National Policy,” San Francisco Examiner, 10 November 1898.

54. “The Greater United States,” San Francisco Examiner, 28 May 1916.

55. See San Francisco Examiner, 14, 18, and 28 January 1917.

56. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst, 353.

57. Editorial published in Hearst newspapers, 29 June 1924.

58. Signed editorial in Hearst newspapers, 31 July 1938. Hearst appears not to have been anti-Semitic; many of his most trusted lieutenants were Jewish, and he advocated a Jewish homeland in Africa or Palestine.

59. Mussolini held banquets in Hearst’s honor in 1930 and 1 931. See Mussolini papers, Psychological Warfare Branch (P.W .B.), report No. 46, National Archives, Suitland, Md. Ambassador to Germany William E. Dodd reported that Hearst syndicated Mussolini for a dollar a word, and that “a Pacific coast bank had loaned Hearst some millions of dollars and that this bank was in sympathy with Mussolini.” The bank was A.P. G iannini’s Bank of America. See Dodd, Ambassador Dodd’s Diary, 220-21; and Bonadio, A. P. Giannini, 134-35.

60. Hearst, “Imperialism,” in Selections, 278-79.

61. The first quote is from Hearst, “The Yellow Peril,” in Selections, 582. The second is from a signed editorial, Hearst, “Washington Disarmament Conference,” in Selections, 194 .

62. Hearst, “In the News,” in Selections, 683.

63. Neylan made the cover of Time on April 29, 1935.

64. Fortune reported as late as 1935 that Hearst held perhaps $ 5 million worth of Homestake stock and no one knew how much of Cerro de Pasco. “Hearst,” 48.

65. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst, 476. See detailed chapter on “Hearst and the Mexican Forgeries” in Sharbach, “Stereoty pes of Latin America,” 109-34.

66. Rickard, Retrospect, 108-9. Rickard especially valued lucid writing and reasoning and wrote books on the subject.

67. Entire nations banned Hearst publications at various times , among them Canada, because of a Hearst campaign to annex that country.

68. Seldes, Lords of the Press, 232.

69. It could be argued that the closely controlled Hearst mining towns provided a model for a more national form of fascism . See Creel, “Hearst-Owned Town of Lead,” 580-82.

70. “Fascism,” Hearst newspapers, 26 November 1934.

71. Signed editorial in Hearst papers, 23 July 1934 . Hearst often blamed communism, which he likened to disease and insanity, for fascism; he wrote from Germany in 1934, “Perhaps the only way to restrain anyone in an hysterical frenzy [of communism ] is in a strait jacket until he recovers his sanity.” Coblentz, William Randolph Hearst, 114.

72. Lundberg, Imperial Hearst, 3 52- 53. George Seldes repeats the cha rge in greater detail in “Hearst and Hitler,” 1-3, and in Witness to a Century, 474.

73. See Hearst newspapers for November 4, December 2, December 30, 1934, and February 24, 1935. For other citations, see George Seldes, “How Hearst Fed Nazi Propaganda to 30,000,000,” in In Fact, 13 March 1944; and George Seldes, “Hearst Charged with Treason,” in In Fact , 20 March 1 944. See also Dodd, Ambassador Dodd’s Diary, 21 4, 220-21, 254.

74. “Hearst,” Fortune, 43-1 60.

75. Ibid., 158.

76. Lundberg, Imperial Hearst, 309.

77. “Hearst,” Fortune, 140.

78. Winkler, William Randolph Hearst, 1. In 1 944, for example, he cabled Edward Hardy Clark about a Mexican property he wanted him to investigate: “I am very much interested in the Acapulco gold mining property for several reasons: I like gold mines and I like Acapulco.” William Randolph Hearst to Edward Hardy Clark, 10 January 1944. William Randolph Hearst papers, carton 40, Edward Hardy Clark file.

79. William Randolph Hearst to George Hearst, 4 January 1885, Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers, box 63.

80. Signed editorial in San Francisco Call & Post, 1 June 1918.

81. “American Architecture,” editorial published in Hearst newspapers, 29 May 1927.

82. Martin Huberth to William Randolph Hearst, 19 May 1 928, William Randolph Hearst papers, carton 49, “Real Estate.”

83. “Support Contras,” San Francisco Examiner, 21 April 1 985.

84. Lundberg, Imperial Hearst, 264.

85. On February 2, 1998, nine days after the kickoff of a three-year commemoration of Marshall’s discovery of gold and the rush that followed, the r50th anniversary of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo went almost wholly unremarked in California. On May 1, 1 998, San Francisco newspapers similarly forgot the centennial of Dewey’s victory at Manila and the beginning of the Spanish-American War.

86. “A Historic Name, a Futuristic Vision,” New York Times, 24 April, 1994.

A note on the Notes

The notes for this and all other chapters are organised by subsections. Not all subsections have notes. It has not been possible to replicate the context of each note. For context, please refer if possible to the print edition. More information on all the materials cited is available on the further reading page.

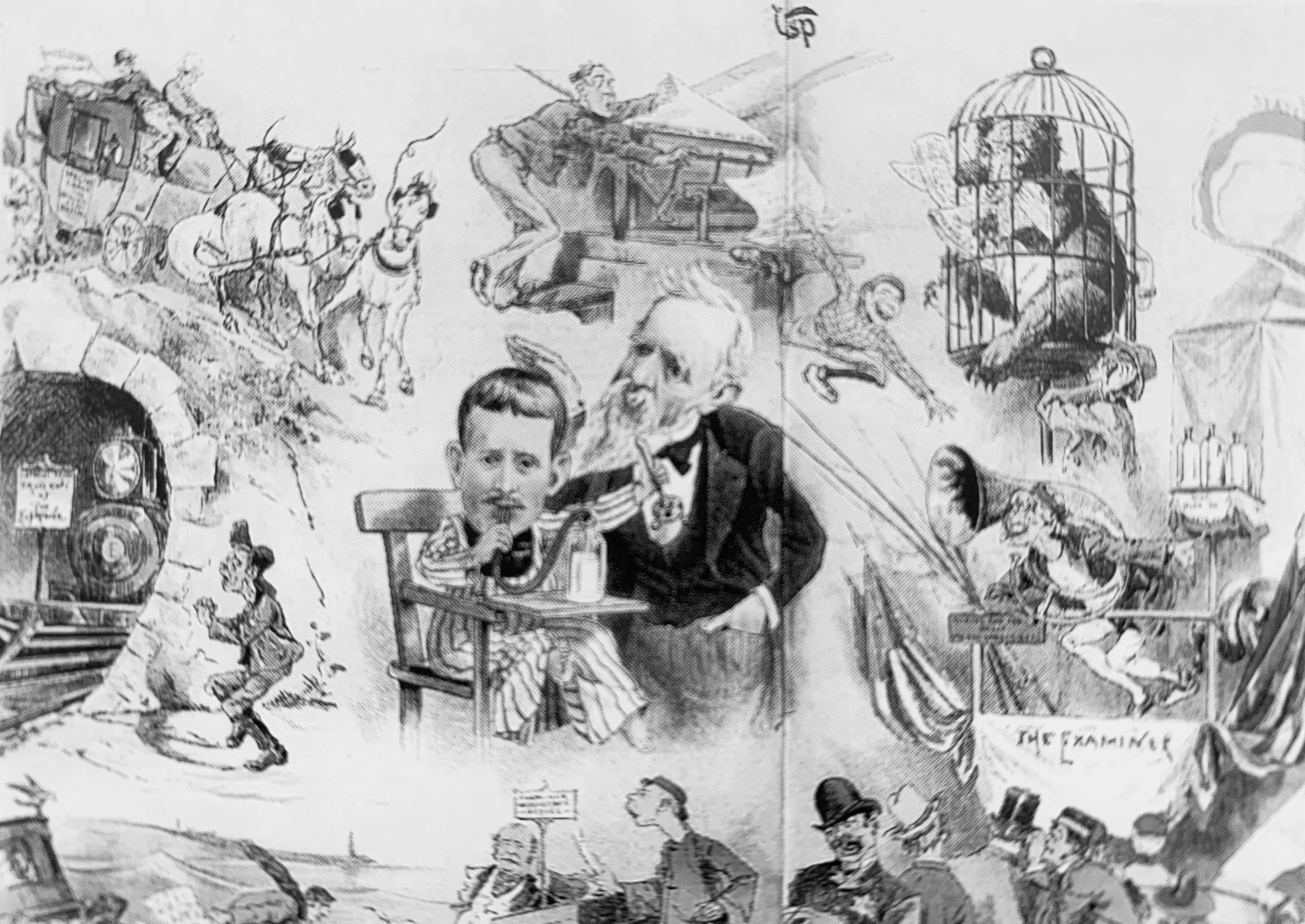

An indulgent Phoebe Apperson Hearst and her willful son, William Randolph, relax at her suburban hacienda south of San Francisco. Courtesy University of California Archives.

“Juvenile Journalism.” Young “Willie” Hearst as a spoiled toddler backed by the mining millions of his indulgent father is surrounded by the expensive journalistic stunts that enabled the Examiner to surpass the circulation of Michael de Young’s Chronicle. The Wasp, February 15, 1890. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

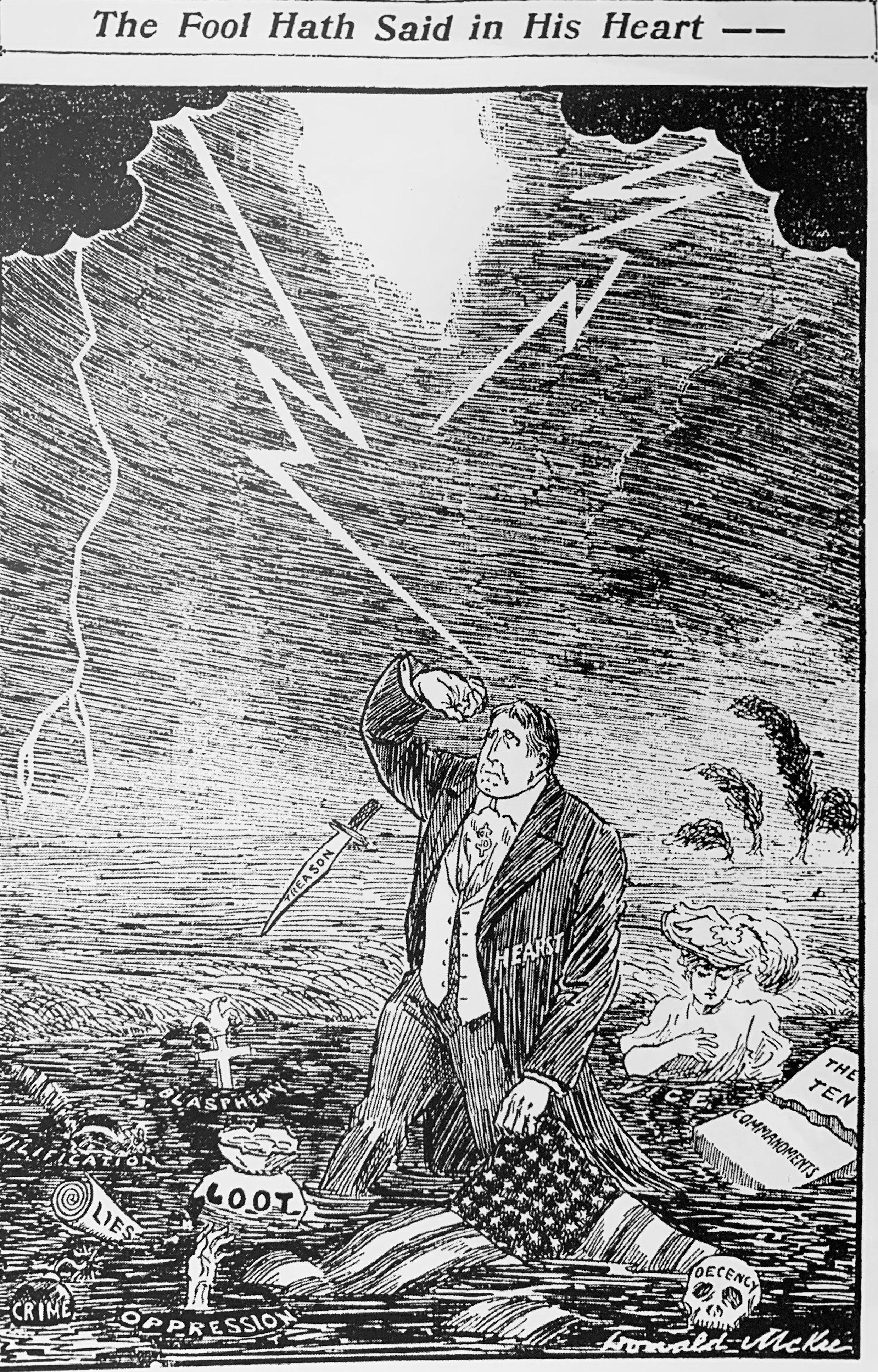

“The Fool Hath Said in His Heart-.” As Hearst’s power and political aspirations grew, so did the attacks on him for his activist style of yel low journalism. Here, candidate Hearst wades through a swamp of vice, loot, lies, crime, oppression, treason, and blasphemy in an editorial cartoon from the Spreckels’s rival newspaper. San Francisco Call, October 11, 1908

“A Pleasant Dream.” Uncle Sam feeds a dove of peace while a Japanese soldier stealthily prepares to stab him in the back. San Francisco Examiner, May 2, 1916.