Chapter 4

The De Youngs:

Society Invents Itself

Three brothers of mysterious heritage founded what was to become the West’s leading daily newspaper and opinion-shaper during the Civil War. Mayhem and insanity eliminated two of them to leave Michael De Young to battle rival newspapers owned by the powerful Hearst and Spreckels families, all with their own extensive interests little known to their readers. Those self-interests are examined as the basis not only of dynastic wealth and power but of thought-control for the benefit of those who own mass media to the present. The De Young name endures today only as applied to the city’s eponymous art museum.

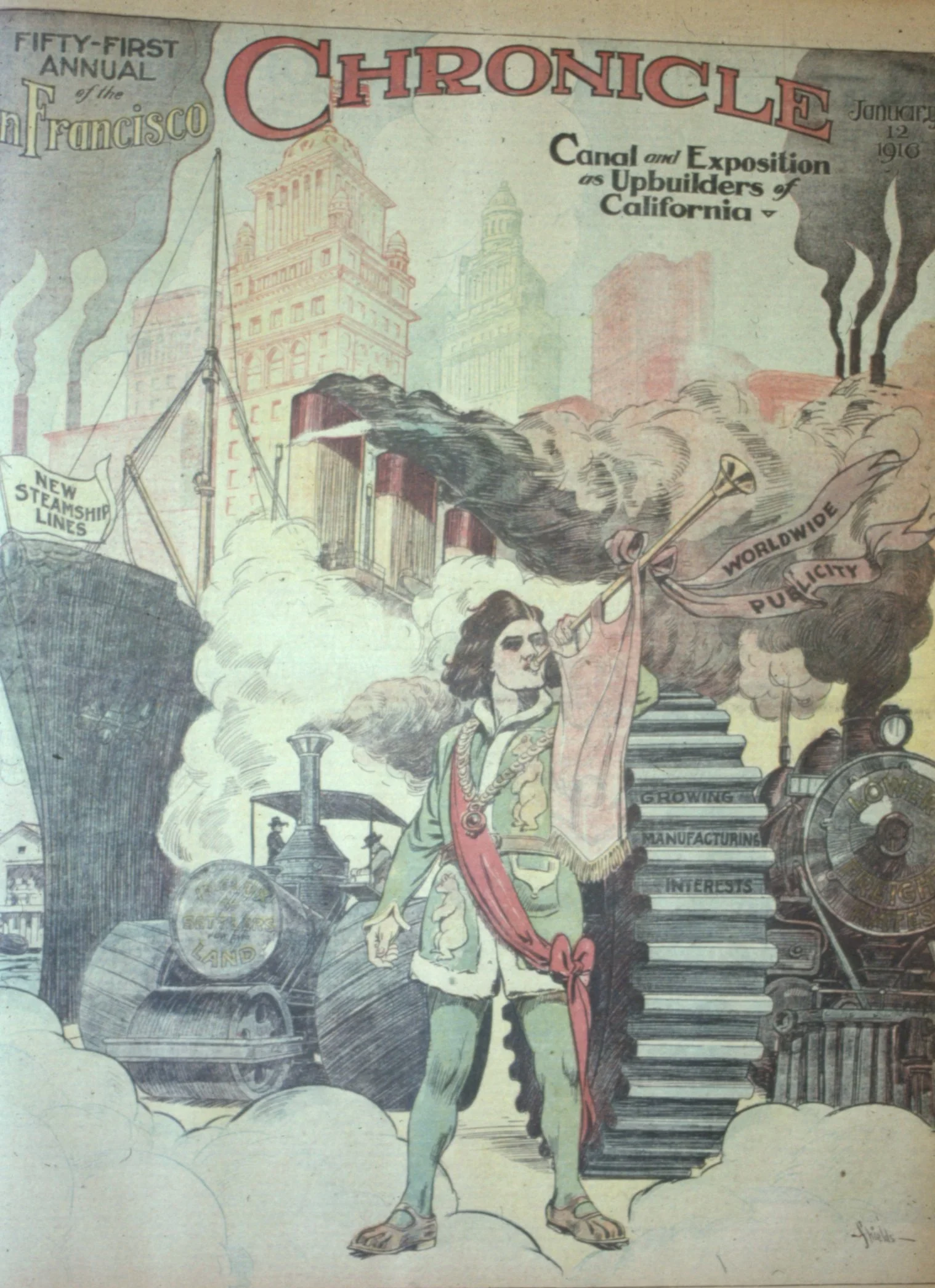

As the century turned, the Chronicle looked forward to “The Imperial Future of California.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 31, 1899. Courtesy California State Library.

Notes

1. Richard T. Thieriot, “125 Years of the Chronicle,” San Francisco Chronicle, 14 January 1990.

2. Rosenwaike, “Parentage and Early Years,” 210-17. The author admits the difficulties presented by researching the de Youngs. The family papers are not available to the public.

3. For those clubs that long limited or excluded Jews, see Narrell, Our City, 404-5.

4. Anderson, “Blue Pencil,” 1 93.

5. “The Course of True Love,” San Francisco Chronicle, 17 October 1869.

6. McKee, “Shooting of Charles de Young,” 275-76.

7. G. H. Smith, History of the Comstock Lode, r80. (Smith cites the Alta California, 13 January 1877.)

8. G.H. Smith, History of the Comstock Lode, 169, 17 1-75.

9. Michael de Young’s obituary reported that he had for eight years been a member of the Republican national committee, attending four national conventions as California’s delegate. An 1891 broadside, “Mike,” by Frederick Perkins, charged, “He has received (it is said), $60,000 per campaign for supporting the Republican party.”

10. Wasp, 18 July 1 885. See this issue for a cartoon of de Young pelted with eggs and tomatoes by a mob.

11. John and Adolph Spreckels also owned the two leading newspapers of San Diego, a city they hoped to make a rival of San Francisco.

12. In this, as in so much else, de Young appears to have followed custom. Upton Sinclair notes of William Randolph Hearst, “When Hearst ventured to run for governor of New York State, his enemies brought out against him a mass of evidence, showing that he had deliberately organized his newspapers so that the corporations which published them owned no property, and children who h ad been run down and crippled for life by Mr. Hearst’s delivery -wagons could collect no damages from him.” Sinclair, Brass Check, 338.

13. Chandler and Nathan, Fantastic Fair, 5.

14. Arthur McEwen ‘s Letter 1, no. 4 (1o March 1894): 3.

15. United Brotherhood of Labor, “Facts Concerning the Midwinter Fair,” 9 September 1893.

16. See Hicks-Judd Company, San Francisco Block Books (San Francisco: Hicks-Judd Company ), for 1901 and 1909. Earlier block books do not include the Outside Lands. De Young’s extensive landholdings within San Francisco are difficult to determine; while lists of property were compiled by the city following the 1906 disaster (the McEnerney Index ), de Young’s file is missing from the Recorder’s Office.

17. Perkins, “Mike.”

18. Arthur McEwen’s Letter r, no. 3 (3 March 1894 ): 2.

19. Bierce’s poem “A Lifted Finger” concludes, “A dream of broken necks and swollen tongues- / The whole world’s gibbets loaded with De Youngs!”

20. Some enemies said that Mike had had his brother committed to get him out of the way. Gus de Young died at the asylum in 1906 . Michael went to Stockton to collect the remains, but the Chronicle ran no death notice . See “Gustavus De Young Dead,” San Francisco Call,13 October 1906.

21. Arthur McEwen Answered r, no. 1 ( 10 March 1894 ).

22. J .A. Hart, In Our Second Century, 1 90.

23. Cameron, Nineteen Nineteen, 13.

24. The museum didn’t officially acquire the name M.H. de Young Memorial Museum until 1924.

25. In this vein, mayors have called both Market Street and Van Ness Avenue the Champs Elysees of the West since at least the turn of the century, a prime example of wishful thinking. See also Kate Atkinson, “What Being ‘The Paris of America’ Really Means,” San Francisco Call, 5 June 1910, for its allusion to vice.

26. San Francisco Chronicle, 3 1December 1899. See also “Our Money Making Commerce with the Philip pines,” 1 January 1904; and the editorial “The Philippine Islands,” 23 October 191 3.

27. “M.H. De Young Says ‘Advertise,”‘ Merchants’ Association Review 8, no. 89 (January 1904 ): 6-7. See also Land Show edition of the San Francisco Chronicle, 19 October 19 13, and issues for a week before and after the show, which specifically promote San Franciscan and Californian real estate.

28. Horace R. Hudson, “San Francisco of a Century Hence,” San Francisco Chronicle, 1January 1904.

29. Professor Edward Alsworth Ross wrote in19r o, “Thirty years ago, advertising y ielded less than half of the earnings of the daily newspapers . Today it y ields at least two-thirds. In the larger dailies, the receipts from advertisers are several times the receipts from the readers, in some cases constituting ninety percent of the total revenues. As the newspaper expands to eight, twelve, and sixteen pages, while the price sinks to three cents, two cents, one cent, the time comes when the advertisers support the paper. The readers are there to read, not to provide funds. “ Ross, “Suppression of Important News,” 304.

30. Spreckels was the estranged maverick son of the sugar king Claus Spreckels. He and Phelan were partners in the Real Property Investment Corporation, which bought much of the land from the Fair estate. “Spreckels-Phelan-Magee Syndicate Incorporated, “ San Francisco Chronicle, 5 October 1904.

31. Roosevelt to Spreckels, 8 June 1908, quoted in Hichborn, “The System, “ xxv-xxvi.

32. Steffens, Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, 567.

33. “The Moral Issue Be Damned,” San Francisco Call, 25 November 1907.

34. San Francisco Call, 2 June 1907.

35. San Francisco Call , 9 February 1908.

36. Steffens, Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens, 570-71.

37. Older and his wife narrowly escaped a bombing, after which the editor was kidnapped, then rescued from a train headed for Los Angeles. Prosecuting attorney Francis Heney was nearly fatally shot in the courtroom, and key witnesses and suspects after vanishing were found floating in the bay.

38. Older, My Own Story, 1 96.

39. Bean, Boss Ruef’s San Francisco, 303-4.

40. “First of Solano Farm Suits Is Quickly Dismissed,” San Francisco Chronicle, 25 October 1916.

41. “De Young Sued for $180,000,” San Francisco Examiner, 22 January 1916.

42. Sinclair, Brass Check, 24 I.

43. Anderson, “Blue Pencil,” 1 92.

44. Arthur McEwen’s Letter, 1, no. 2 (24 February 1894): 1. De Young was, for twenty-three years, director of Associated Press. Upton Sinclair cited a 1909 study in La Follette ‘s Magazine which showed how the fifteen directors of the Associated Press, all publishers of major newspapers and all politically conservative to ultraconservative, filtered the news. According to the article’s author, they were all “huge commercial ventures, connected by advertising and in other ways with banks, trust companies, railway and city utility companies, department stores, and manufacturing enterprises. They reflect the system which supports them” (emphasis added). “In other ways” often included marriage, as demonstrated by the de Young family. Sinclair, Brass Check, 275.

45. “Purchase of Newspaper Another Triumph for Noted Coast Journalist,” San Francisco Call, 15 August 1913.

46. The kidnapping of Patty Hearst provided an exception, focusing international attention on that family.

47. “[The assistant managing editor] is versed in a most essential knowledge of what may be printed in the paper, and what it would be dangerous for the public to know. Under his care comes the immense problem of general policy, the direction of opinion in the city in the paths most favorable to his master’s fame and fortune.” Anderson, “Blue Pencil, “ 192.

48. Wall Street Journal, 7 July 1983; and Carol Benfell, “Newspapers in

S.F. Seek Expunging of Trial Evidence,” Oakland Tribune, 17 July 1983. For some of Sheldon Cooper’s interests, see his obituary, San Francisco Chronicle, 12 November 1990.

49. Other reasons are given by Hensher, “Penny Papers,” 162-69.

50. Vanderbilt, Farewell to Fifth Avenue, 242.

51. Michael de Young’s only son, Charles, died childless in 1913. The Spreckels name has also died out. William Randolph Hearst produced five sons, however, and the Hearst name endures.

52. Winter, Metamorphosis of a Newspaper, 25. Governor Earl Warren’s secretary recalled that the three families who owned the Oakland Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle were once known as “the axis” of California, since they picked governors and ran California for the Republican Party. See Small, “Merrell Farnham Small,” 149. Upon her death in r969, Helen de Young Cameron left an estate valued at over $16 million, with stock in seventy corporations.

53. The Chronicle columnist Herb Caen reiterated the theme when he wrote of the 1996 opera and symphony openings, “It was Homecoming Week last week for San Francisco’s bon ton, the most incestuous provincials you’d ever care to meet, not that they’re especially interested in meeting you.”

54. A Southern family, the Parrotts had made their money in plantations and the slave trade, expanded it in Mexico, and invested wisely in San Francisco real estate during the gold rush. “Cholly Francisco,” “Engagement of Miss De Young Is Announced,” San Francisco Examiner, 1 January 1914.

55. Cousins, the Christian de Guignes of Hillsborough’s “Guignecourt,” Pebble Beach, and Chateau Senejac in France owned the multinational Stauffer Chemical Company, founded at the turn of the century in Richmond. In 1 985, Cheseborough Ponds bought Stauffer for $ 1.2 5 billion. The first Christian de Guigne also collaborated closely with Henry Huntington in the creation of Los Angeles.

56. In June 1 994, T hieriot’s friend Governor Pete Wilson appointed him to the state Fish and Game Commission. The Chronicle endorsed Wilson in the November election.

57. Peter Waldman, “New Matriarch Minds the Family Business,” Wall Street Journal, 7 July 1 988.

58. Her son Nion’s 7 percent gave the two of them one-third control of the Chronicle companies.

59. Patrick M. Reilly, “‘Black Sheep’ of Family Battles Kin for Control of Newspaper Dynasty,” Wall Street Journal, 25 May 1995.

60. “McEvoy Drops Suit against the Chronicle,” San Francisco Chronicle, 26 August 1995.

61. Sinclair, Brass Check, 400.

A note on the Notes

The notes for this and all other chapters are organised by subsections. Not all subsections have notes. It has not been possible to replicate the context of each note. For context, please refer if possible to the print edition. More information on all the materials cited is available on the further reading page.

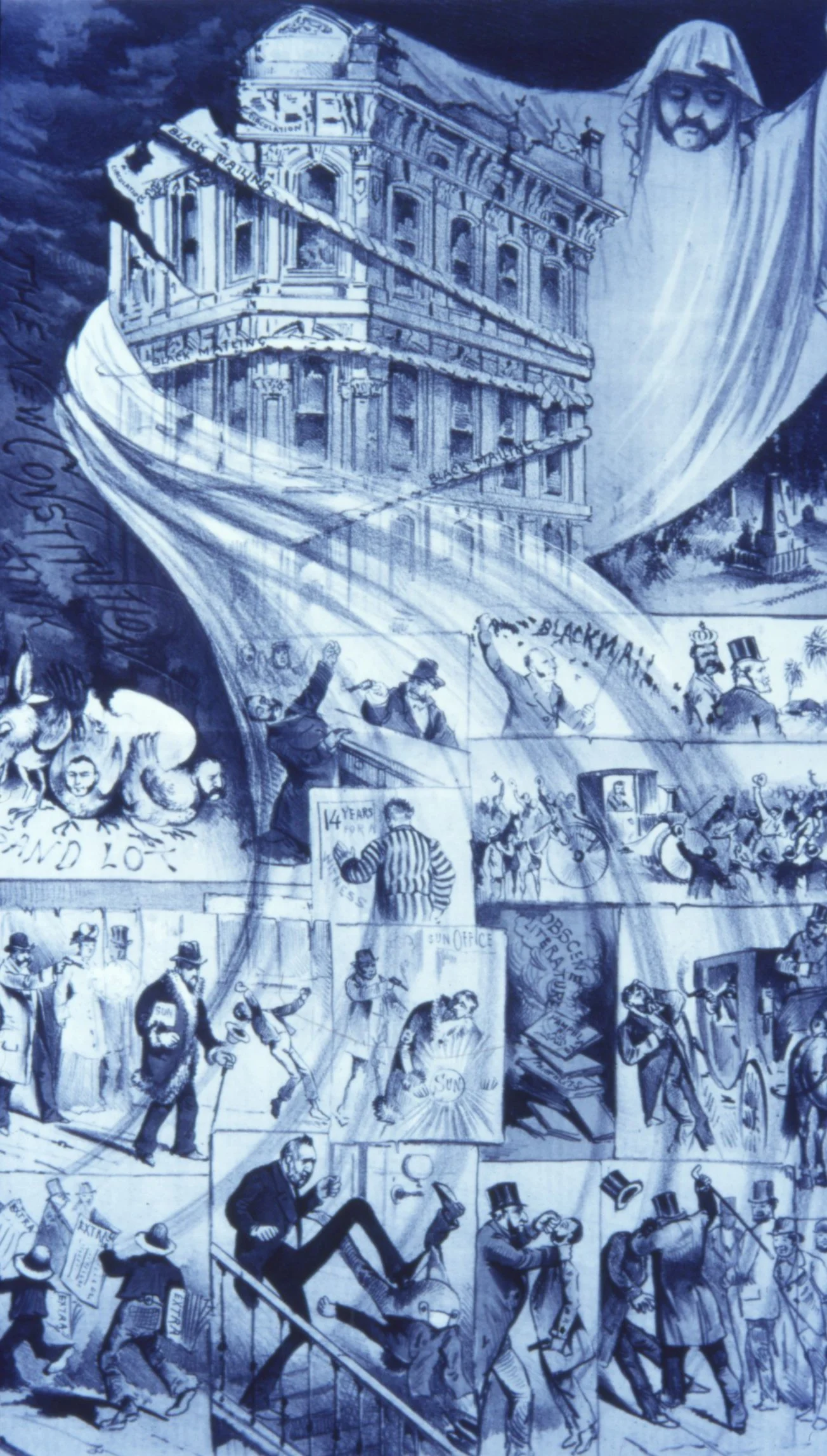

“Pictorial History of a ‘Live Paper.’“ Shortly after his assas sination by the son of a minister whom he failed to kill, the ghost of Charles de Young hovers over the Chronicle Building, contemplating the many acts of violence and blackmail on which the de Young brothers built their newspaper. The Wasp, November 18, 1881. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

John D. Spreckels, Claus Spreckels, and Adolph B. Spreckels. The powerful Spreckels family bought the San Francisco Call in 1895 and used it to reveal details of Michael de Young’s life not published by the Chronicle. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

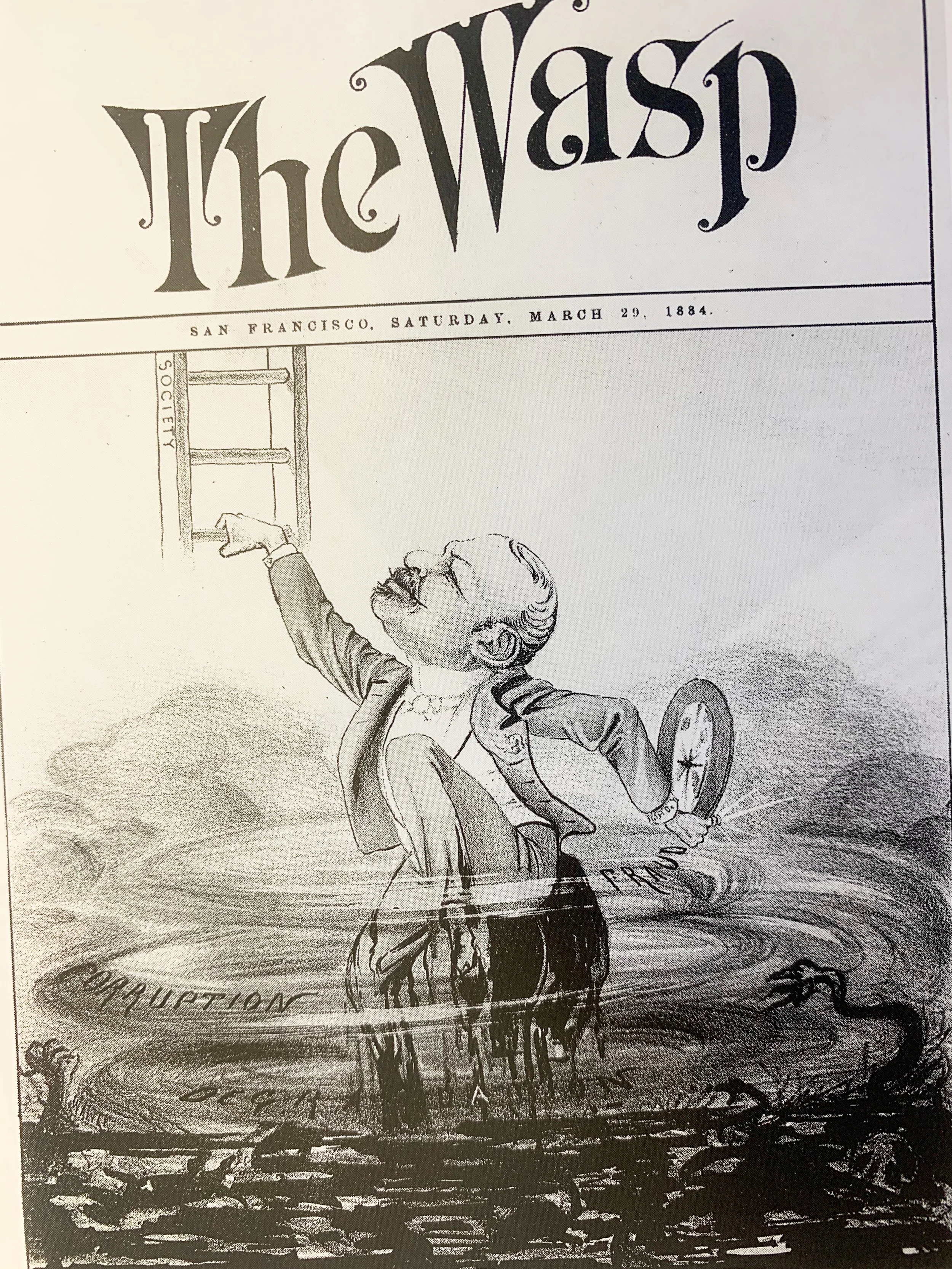

“Out of the Depths.” Michael de Young lifts himself out of a cesspool labeled “Fraud,” “Corruption,” and “Degradation” and onto the first rung of the ladder of San Francisco society. The Wasp, March 29, 1884. Courtesy Bancroft Library.